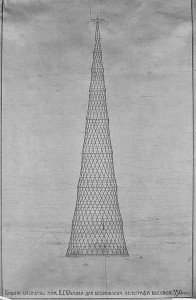

The James Carpenter’s Sky-Reflector Net, erected 2013, within the dome of New York’s Fulton Street Transit Center, has its hourglass hyperbolic shaped roots in the famous Moscow Shukhov Tower, erected in 1920. The 525 foot high Shukov Tower was originally conceived as a 350m (1,148’) radio tower tall enough to reach far off Soviet Territories. Due to WW1 blockades, shortages of materials, and Stalin’s antipathy for the Avant-Garde, it was never completed to its intended height.

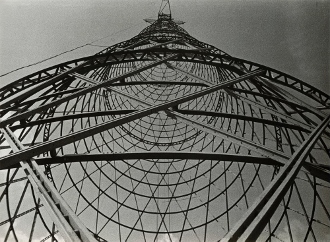

Above, Aleksandr Rodchenko photograph of the Shukhov Tower

Shukhov’s structure was groundbreaking, in the way that it resolved complex engineering principles in a seemingly straight-forward fashion. Hyperbolic structures have a negative Gaussian curvature, meaning they curve inward rather than outward or being straight. As double ruled surfaces, they can be made with a lattice of straight beams, hence are easier to build and, all else equal, stronger than curved surfaces that do not have a ruling and must instead be built with curved beams. A fine article on the finer points of double ruled edges can be found here.

The Shukhov tower survives as a remarkable monument to the Constructivist era, and as a brilliant feat of engineering, both at that time, and now. Although it was intended to be built to a height of 350m, or has high as the Eiffel Tower, it would have barely weighed one-third of that structure’s mass: 2,200 vs. 6,400 tons. This owing to the delicate lattice shells that help to support it. This method was first introduced and patented by Shukov, in 1895, and realized in several structures in Novrogod, 1896.

The Shukhov tower survives as a remarkable monument to the Constructivist era, and as a brilliant feat of engineering, both at that time, and now. Although it was intended to be built to a height of 350m, or has high as the Eiffel Tower, it would have barely weighed one-third of that structure’s mass: 2,200 vs. 6,400 tons. This owing to the delicate lattice shells that help to support it. This method was first introduced and patented by Shukov, in 1895, and realized in several structures in Novrogod, 1896.

The Shukhov Tower inspired other hyperboloid works, such as the Canton Tower, China (2010), and the inelegant Ken Shuttleworth proposed Vortex Tower, London, GB – a knock-off of the earlier glorified scaffold 1987 Kobe Port Tower. Although in 1956, IM Pei proposed his ill-conceived 102 story nuclear bomb-proof hyperboloid tower that would have necessitated the vanquishing of Grand Central Terminal, at that time, the Architectural Record noted the structure resembled “a bundle of sticks,” further sealing its fate. At present, I know of no new hyperboloid structures in the works.

Ironically, all of these Shukhov knock-offs (see video, above) share the same element of hyperbole, or Starchitecture fancy– as it were, absent from Shukhov’s simple elegance. Although works by architects Gaudi, Niemeyer, Le Corbusier, et al., were also hyperbolic in shape, they were decidedly less awe inspiring or ambitious – at least they were modest. At the end of the day, it can be said there has been a startling lack of innovation in hyperboloid design since 1925.

Thus, despite these abortive attempts to match Shukhov’s elegant hyperboloid, there is surprisingly precious little redeeming value in these estimable ventures. Perhaps it is the ill-conceived notion to try to repurpose the hyperboloid structure into functionalities that it simply doesn’t lend itself to, such as offices or hotel rooms. Such programs require beefing up the structure with tons of steel, making them seem lumbering and earthbound.

Which brings us back to Carpenter’s Sky-Reflector Net, which can be taken as a reinterpretation of the hyperboloid structure. In fact, the Sky-reflector net was commissioned as an art piece – part of the Arts for Transit requirement to delegate a percentage of the budget to public art. In this case, about $2.1M, the largest work ever commissioned by that agency. According to my estimates,the installation came in about 25% under budget.

Like the Shukhov Tower, the work also serves a function, albeit less ambitious: its diamond shaped aluminum facets deflect sunlight down into the pavilion from (manually) adjustable reflectors just below the oculus, above. At all of 79 feet in height, the piece is not audacious in height, yet it seems more so when one looks up from the concourse below.

Nor does it, or is it meant to, employ, the same engineering concepts as Shukhov did, in fact, the engineering principles are inverse. Whereas the tower is free standing, and built in compression, the pre-stressed stainless steel net forming the hyperboloid of the Sky-Reflector Net is suspended from circular beams attached to structural steel cantilevers or outriggers. However, the structure of the double-ruled cabling serves to maintain the structural integrity of the netting, without its falling inward toward the cavity. Shukhov used straight angle iron to achieve the same result.

The Shukhov Tower was born of necessity or function. Its design engendered the engineering of a tall, lightweight structure that minimized limited material resources, reduced wind-load and the need for additional bracing. Perhaps, somehow the perfect blend of form and function is why it is such an elusive undertaking to create any hyperboloid structure that may qualify for juxtaposition or consideration next to the Shukov Tower. In this way is the tower sui generis.

Presently, the tower is slated for demolition, as it is in precarious condition. However, The Shukhov Tower Foundation, directed by Vladimir Fyodorovich Shukhov, Shukhov’s great-grandson, advocates for restoration of the tower, as well as the development of a vast multi-use complex. Perhaps, in light of current events in Russia this may be over-aspiring. Nonetheless, there is an argument for the restoration. For more back-story, a bird’s-eye view and tour of the tower, see the recent BBC video on the subject, found in this article.

Below, a Moscow exhibition celebrating Shukhov’s work:

Primer on hyperboliod geometry and application to benign structures

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jymZ060T0iI