A vast majority of projects do not make their finish deadlines. Typically, the owner will seek to back-charge the contractor for the delay, merely by deducting it from his last progress payment or retainer. Depending on the amount, the contractor may or may not put up a fight, and tedious mitigation, arbitration, or even litigation may follow. All too easy for the owner to hold back a payment, it is the rare occasion that a contractor can make – and be paid for disruption claims.

“Disruption is loss of productivity, disturbance, hindrance, or interruption to a contractor’s normal working methods, resulting in lower efficiency. In the construction context, disrupted work is work that is carried out less efficiently than it would have been, had it not been for the cause of the disruption. If caused by the employer, it may give rise to compensation either under the contract or as a breach of contract. ” [i]

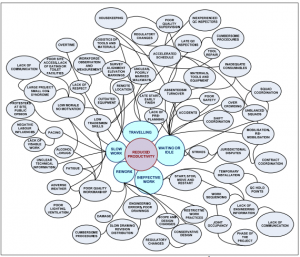

The chart below illustrates the myriad manifestations of disruption that typically effect productivity:

An agent or owner is loathe to honor any such claim, or resorting to litigation is nearly always a low-percentage shot. There are a number of reasons for this. For example, the perception of the mere notion of disruption claim in theory. In Luria Bros. and Co. Inc., v. United States,[iii] the court stated

“quantification of loss of efficiency or impact claims is a particularly and vexing and complex problem. We have recognized that maintain cost records, identifying and separating inefficiency costs to be both impractical and impossible.”

If a contractor claims disruption caused by the owner due to lack of accurate drawings and specifications, he may gain some leverage by invoking the Spearin Doctrine,[iv] which protects against just such circumstance, by requiring complete documentation from the owner to the contractor.

Nowadays, owners have built in provisions into their contract to protect themselves from disruption claims, such as no damages for delay clauses, claims notice provisions, scheduling provisions, claim waivers, and limitation of liability. Although an owner may recognize a disruption of the project for which the contractor is not blameful; such as acts if God, factory delays, etc., he will be loath to compensate the contractor for his extended overhead costs. If the contractor intends to make such a claim, he is typically strapped to make an accurate assessment of damages to substantiate his claim. This becomes an even more protracted reality in mediation and litigation.

For example, if a contract change order is effected for additional scope, the charge may include overhead and profit, which is a percentage or sub-component of the change order. This is additional scope relatively easy to valuate. Owners can understand such a change order, as they note the same mark-ups in the base contract; however, not so a change order for disruption, leading to a loss of productivity, which is comprised only of overhead and other soft-costs, such as insurance, project management, home-office,[v] or carrying a bond. Arguably, the fact that owners typically don’t challenge overhead added to contract change orders seems to me somewhat of a conundrum, since overhead is fairly static, as compared to general conditions. I expect this is because typical contracts stipulate contract change order mark-ups.

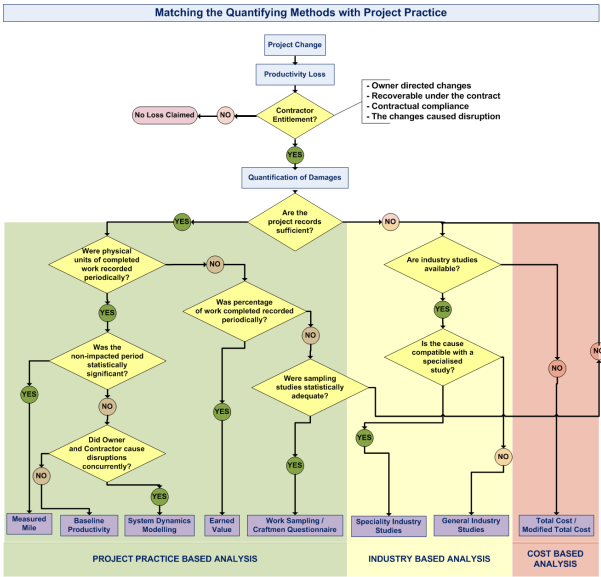

Although valuating disruption claims is difficult to do, it is not impossible. There are a number of methods for quantifying disruption claims, and other elusive cost-over-runs; such as trade-stacking (congestion), decrease of productivity, or other seemingly intangible costs. These methods are recognized by mediators, arbitrators, and the judiciary. Implementing them requires a lot of study that goes beyond the compass of this post; however, I have included them below for future reference, in order of viability. Additional information on these methods is readily available on the Internet, particularly the fine Derek nelson paper referenced in the end-notes:

- Measured Mile: this is the method most recognized and observed by courts

- Industry standards: which quantify labor productivity, for e.g., the MCAA’s productivity factor analysis

- Total-Cost Method: claims that the current project has substantially changed from the original contract, such that they are fundamentally different.

- Modified Total Cost Method: a sub-set calculated from the Total Cost Method

- Jury Verdict: as a last resort, the burden of proof lies with the trier of fact, who must prove that the above methods are not tenable.

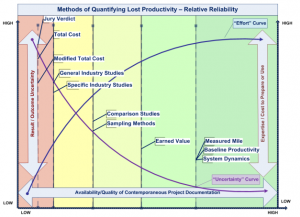

The graph below illustrates

“the relationships between the availability, quality, and providence of the contemporaneous project documentation, the reliability of the methods quantifying lost productivity, and the cost and expertise generally required to record, prepare, and document the quantum damages derived thereby. The horizontal axis refers to the attributes of the project data. The two vertical axes refer to attributes of the methods available for calculating lost productivity. The methods listed typically increase in precision as they move from the top to the bottom in the graph, and from left to right, i.e., from a total cost approach, to a measured mile approach. This also reflects the order of preference in the research literature.[vi].

There is an exigent prerequisite to any disruption claim, and that is a properly tracked schedule, and productivity reports; data which your average contractor is highly unlikely to have in his possession. Without the tracked schedule, a scientific delay calculation becomes a moot point. Moreover, if the disruption is concurrent with the base timeline, or it is not merely an extension added to the end of the contract time, an owner will argue that overhead costs were ongoing, or in place concurrently with the disruption.

Short of availing themselves of recognized scientific methods, there are other ways contractors can protect themselves when they are subject to absorb schedule over-runs. One way is to negotiate a higher overhead rate for change orders in the base contract. Despite the fact that many owners often perceive change orders as price-gouging, or making up for a low-ball bid, most contractors will tell you they lose money on their change orders, due to the higher rate of overhead, or one that is disproportionate to the base-contract rate, and decreased productivity. It must be said that owners are seldom agreeable to this higher rate for overhead built into their contract, but it can’t hurt to try.

[i] Nelson, Derek, “The Analysis and Valuation of Disruption,”(pg. 3) Hill International (2011)

[ii] Dr. Ibbs “Measuring Productivity for Improved Project Performance” (2009)

[iii] Luria and Bros. Co. Inc., v. United States, 177 Ct Cl. 676,

[v] Home-office calculation can be measured using the Eichleay formula, for which a brief paper on that method can be found here

[vi] Nelson, Derek (11)

[vii]Adapted from “Quantified Impacts of Project Change,” Ibbs, Long, Nguyen and Lee, Journal of Professional Issues in Engineering Education and Practice 2007 (Nelson, Derek (11)