Construction site logistics follow some basic operational guidelines that can be categorized according to the nature and location of the work. Urban construction site logistics differ from others in that site footprints are smaller, and the work is vertical. As such, the criteria for urban work site logistics is considerably different from other locations.

Site logistics are critical to facilitating workflow while ensuring the safety of workers, visitors, pedestrians, and traffic. Dense urban areas will require the strictest compliance and enforcement with safety measures. As part of enforcement, officers from the respective agencies make frequent visits in order to monitor compliance with site safety plans (SSPs) and other engineered programs.

Surprisingly enough, the Construction Specifications Institute (CSI) Masterformat is fairly reticent on the topic of “site logistics,” preferring to categorize cranes and such under the dubious subheadings ‘Temporary Facilities and Controls: 01 53 00 Temporary Construction, and 01 54 00 Construction Aids.’ In lieu of comprehensive specifications, an engineer’s logistic plan will take precedence. Contractors include costs for site logistics variously under general conditions and overhead.

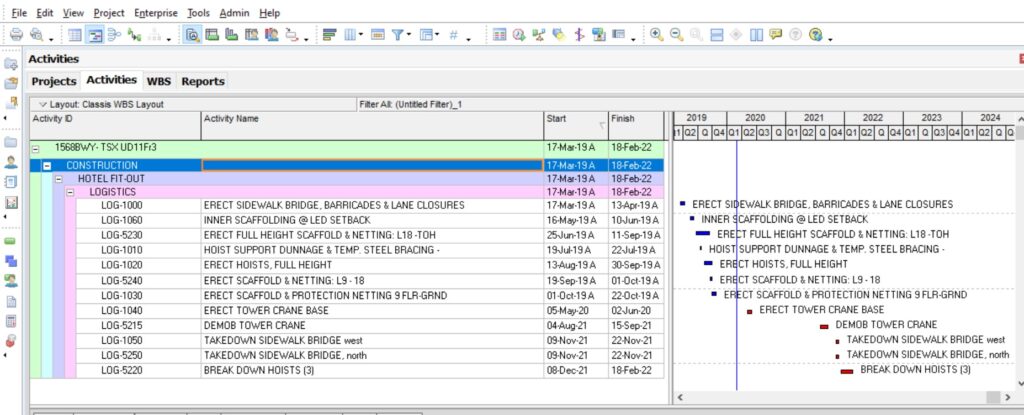

Aside from basic requirements, the installation and maintenance of a given project will be tailored according to respective project criteria: location and program. Site logistics must be represented in the baseline construction schedule, as they drive critical-path structural operations, and could potentially delay mobilization. Site logistics may include location of

- Hoistways

- Cranes

- Scaffolds

- Sidewalk bridges

- Roadway access for delivery and hauling operations

- Controlled access points

Logistic design plans are issued with the bid set. These are prepared by engineers who are fluent in local codes and safety requirements. They are intended to impart a general and high-level sense of where major equipment – cranes and hoists, and protective measures – fencing, scaffold, sidewalk sheds, are to be placed within a surveyed area taken and site plan. The earthwork, concrete, and steel trades, prepare the working logistics plan for permit applications and construction. Agency review periods should also be represented in the baseline schedule’

Before cranes and hoists bases are anchored support of excavation (SOE) for new foundations is mobilized to facilitate earthwork – excavators and front-loaders. The trades will want to efficiently mobilize as much equipment as possible without stepping on their own shoes. This can be a challenging dance on sites with small footprints. It’s not unusual to see excavators, impact hammers, drilling rigs, and front-loaders, compete for space alongside concrete pouring or grouting operations.

Up on grade, access roads are carefully coordinated to orchestrate the movement of concrete and steel material and equipment coming in, and debris haulers rolling out. This interior traffic coordination is mission critical – the danger being the bottlenecking and backing up of site resources and exterior traffic patterns.

The trades will submit a logistic plan for approval that represents implementation of logistics and SSPs together. These plans will include interior traffic patterns for loading, delivery, and hauling. At this time, it’s important to plan the positioning of required compressors, generators, and pumps, with the logistics plan, in such a way that they don’t impede movement or need to be repositioned.

Dense urban site logistics begin with safing off the site, which includes erection of barricades separating the public, maintenance and protection of traffic measures (MPT). MPT may include road barriers, flagmen, tow-plates, sidewalk bridges, and signage, pylons and road-striping for lane closures and redirection, which may be for all or partial segments of the construction period.

Upon the sidewalk bridges under which pedestrians walk, scaffolding is erected and braced to the structure. There are several types of scaffolding, chiefly tube-and-clip, systems, hanging or suspended, mast, and climbing. These are also referred to variously as

- Single Scaffolding

- Double Scaffolding

- Cantilever Scaffolding

- Suspended Scaffolding

- Trestle Scaffolding

- Steel Scaffolding

- Patented Scaffolding

Each system has its own advantages and drawbacks, as well as distinct means and methods of erection, raising or ‘jumping,’ and removal. Vertical access sequence of operations is generally addressed in brief in the schedule, because it’s tedious and difficult to anticipate the timing of every movement. It’s also unnecessary, because progression of work drives erection. Staging of scaffolding (and cranes and hoists) are facilitating operations that are intended to proceed without interrupting the work-flow, or getting mixed-up in the critical path. Unlike consecutive hoist staging, a crane jumps fifty or sixty feet at once. Jumps can be done at night or early morning so as not to disrupt workflow.

Scaffolding and hoists are brought up as high as possible and allowable to working platform heights to facilitate the movement of workers, equipment, and material. If they are too far below, work will continue above, albeit at reduced production owing to extra stairways for workers to traverse. Each working platform must have safety railing around it, tie-off points for worker PPE, and debris netting below the perimeter.

All site logistics operations require engineer approval, but more importantly, multiple agency approval. For example, New York City approvals may include Department of Buildings, Cranes and Derricks, Department of Transportation, Fire Department, as well as neighborhood and public advocacy organizations. These approval dates should be tracked beginning with the baseline schedule. These permits must be renewed before they are allowed to lapse, lest a stop-work-order (SWO) be issued, along with a fine.

Site logistics operations can affect the fit-out of a project by encroaching on working floor space – specifically, bracing and tiebacks for vertical access. Standing cranes and hoists use steel members for stabilization that are spaced according to engineered designs, for example, every sixty-feet. If not placed with care, these members can inhibit interior programs. It’s not unusual to see blanks in curtain wall placement to accommodate tie-backs, or hoistway walk-off ramps. The panels are later placed as ‘come-back’ work.

Another challenge of curtain wall logistics is coordinating delivery and installation of panels from the interior. Interior loaded panel installation is frequently a necessity where there is insufficient space or clearance outside to swing a crane. If the panels arrive too soon, they inhibit layout and other early rough work, and are subject to damage. If framing and other work is mobilized before the panels are delivered, this work can inhibit the distribution and placement of the panels. For this reason, few builders frame interior walls before the curtain wall is installed.

Depending on the system, a curtain wall may be a stick or unitized assembly. Stick systems are cut to size extrusions, assembled on site, installed, glazed and waterproofed. Stick systems require far more assembly time on site than do unitized. A good rule of thumb is a 70/30 factory to site labor ratio for unitized systems, and a 30/70 ratio for stick systems. The exception is for oversized and specialty panels set into structural framing. One such example is the street elevation for the Fulton Transit Center – both oversize and explosion-rated glass within structural mullions.

Unitized curtain walls offer a sleeker look, and superior waterproofing performance and warranties than stick systems, however, they cannot be modified on site. Unitized systems are factory pre-assembled. Systems at the lower floors can be placed with mobile equipment – such as a crawler crane, whereas higher elevations may be set with a mast or tower crane from the exterior, or dropped down from above using a motorized winch. Adequate clearance space for the winch rig, counterweights, and operating crew should be coordinated with interior operations.

Balcony panels take longer to install than do stacked panels, as they must fit snugly between the top of one slab and the underside of another above. Transitions and corners can be more challenging for unitized systems, which cannot be adapted on site. Any curtain wall panel covering a shear wall is typically a metal or glazed blank that must be fitted from the exterior, typically with a swing stage scaffold. As such, the embeds or anchor bolts for these panels are cantilevered.

The careless choice of location for a crane or hoist can come back to haunt a project. For example, a recent project located its crane pad and caissons directly over the point of entry (POE) for several utilities. Because this conflict was discovered too late, costly workarounds of temporary service and modifications had to be introduced to mitigate certain delays. Had the electrician been invited to review the logistics plan perhaps this problem could have been easily obviated.

One final – if little attended – nuance of logistics, concerns the uninhibited movement of personnel, equipment and materials. Typically given short shrift, the free and expedient movement of these resources should be developed with much consideration. It’s not due diligence to simply mobilize hoists based on a theoretical calculation and hope they will be sufficient to the purpose. Care must be taken to factor in wait and travel times at various phases of the project. Naturally, there will be days when a hoist is taken out of service, a circumstance that exacerbates productivity loss.

The level of resources moving up and down on a project affects the rate at which the hoists and elevators can move them. Too often it becomes clear that this factor is an oversight resulting in severe slowdowns that directly diminish efficiency. For example, no one could have planned for the new social distancing rules of COVID-19 that increase costs (by early appraisals) of 18-20%, however, traditional hoist wait-times pre-COVID were already commonplace.

It’s an oversight when workers wait for thirty-minutes for a ride on a hoist between floors or returning from lunch or coffee owing to poor planning, or because deliveries jam the loading dock. I like to introduce staggered break times to reduce these delays, and designated times for deliveries such that they don’t interfere with personnel movement. These seemingly mundane delays are seldom quantified into cost at the peril of the general contractor.

Few of these logistic sequences and mitigation plans are the bailiwick of the scheduler, however, it is the rare superintendent or project manager who raises the question in the first place. For that reason, it pays to have a scheduler with hands-on experience, who can anticipate and foresee these challenges and take it upon himself to raise the issue, perhaps meet with the trades to discuss means and methods. There’s nothing in the PMI or AACE manuals that says he can’t. It also wouldn’t hurt to recommend due diligent logistics coordination in the schedule as best practice.