Every out-of-the-ground building has its own unique substructure profile, or site class, that is addressed by a structural engineer. Nowhere are substructure profiles more complex than in urban environments, where building substructures must coordinate with utilities, tunnels, and existing building substructures. And no urban environment is more complex than New York City (see above). Thus, the site characteristics must be included as a critical part of planning and scheduling.

The focus of concern of subsurface profiles is divided into three strata, from sea level down about 800 feet. Level I – to -30 feet – will include utilities, stacked form top down: electrical, signal (CCTV), water, steam, and gas. Level II = about -30 to -200 is where subway tunneling is found, and Level III – -200 to -800 sewage and deepwater tables. These programs are all a matter of public record, however, they aren’t always comprehensive.

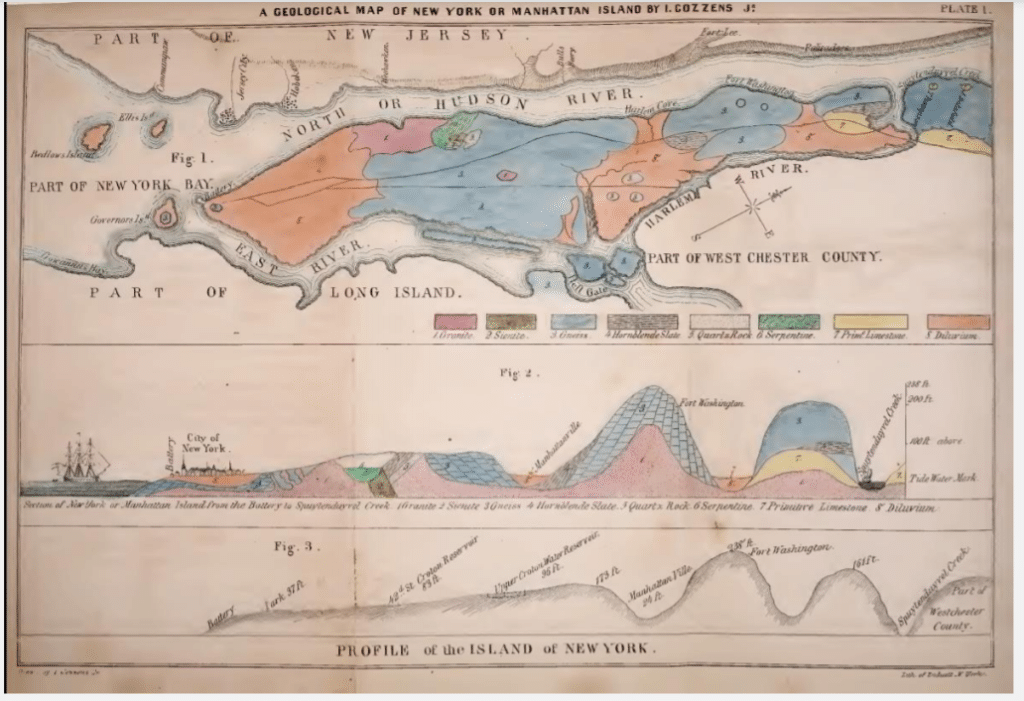

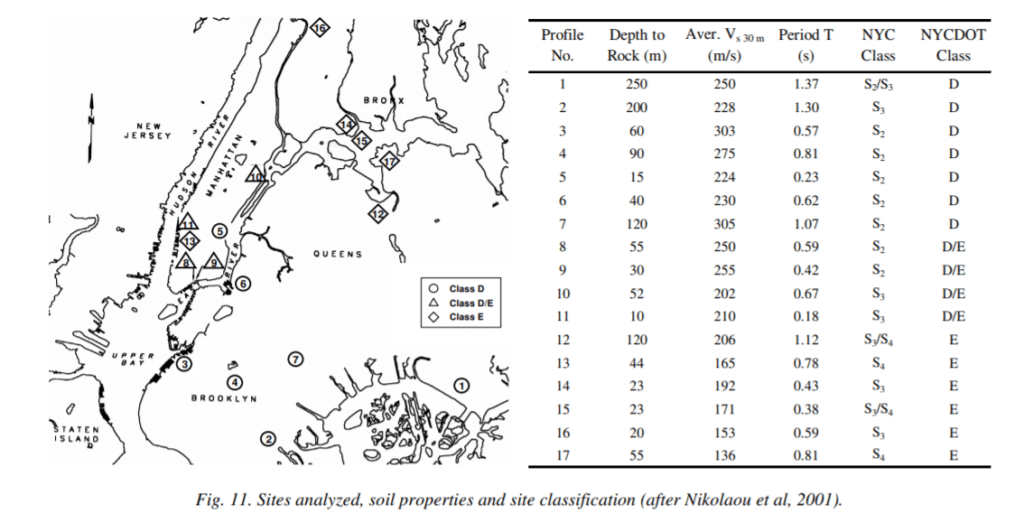

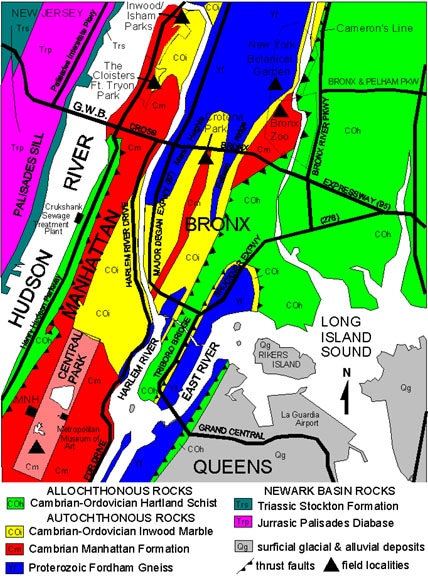

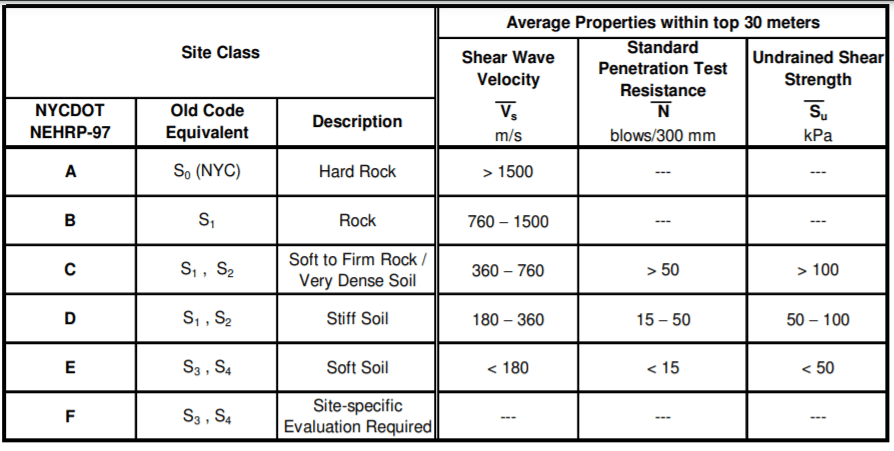

While there are circumstances that are unique to every project, most subsurfaces are largely predictable from geological profiles. However, there are some basic similarities that all projects share, that can help to illuminate both the obvious and not so obvious considerations. These begin with the geological profile, which is informed by boring logs that record the material encountered in core sections and recorded in reports that engineers base their design and calculations on.

Manhattan island features several geological profiles that each dictate criteria for substructure support as well as risks associated with those profiles, which vary from bedrock, to silt and clay, and finally sand-fill, such as those used in Lower Manhattan, JFK Airport, and the US Tennis Center. Within various bedrocks, drilling productivity will vary according to hardness. In loose soils adequate compaction may not be achievable. Many excavations hit water tables, which require dewatering operations. The strategy for tunneling will vary from tunnel boring machines for solid soil and rock, to cut and cover for open mass excavations.

Excavations for new buildings are usually predicated on availability of a site. In NYC, there are few extant virgin sites, and most structures are built over pre-existing ones, or disturbed substrate. Disturbance depth is relative to the height of pre-existing structures. This is relevant insofar as new substructures are concerned: the depth at which undisturbed soil or bedrock is encountered and deemed suitable for piles or caissons to support building load. In some cases, suitable substrate is simply too far below, and other means – such as monoslabs are employed in lieu of piles or caissons.

Once a site is secured, it is prepared for excavation. Digging and removals are done in tandem with support of excavation (SOE), which often includes underpinning of adjacent structures. Structural engineers study available drawings to determine as best they can where adjoining substructures may come into conflict with excavation. They also rely on boring reports to convey critical information about the substrate profiles: the physical and geological characteristics of the soil from grade, and down as much as three-hundred feet, in order to plan the design and location of piles, caissons, and foundations.

Once mass excavation is complete, drilling for piling and caissons takes place. At this time, the boring logs will inform a contractor of where he can drill and where not to: where soil is too loose or wet, or where boring was encumbered (refused). Few sites are without surprises – such as undocumented abandoned piles and foundations, debris, fuel tanks, or even burial grounds. This latter condition can sideline a project for great lengths of time until resolution of action can be developed and agreed upon.

Once a site is cleared for drilling, it’s mostly a matter of logistics that determine the most efficient approach. Many considerations come into play that should be coordinated into the project schedule. Caissons and piles need to be ordered and prosecuted in such a way that they don’t impede progress. That includes ensuring that large drilling rigs are able to freely manoeuvre around grouted piles, and that holes are far enough apart that they don’t ‘communicate’ with, or disturb each other.

The wild-card in all of this process is coordination with various agencies that have an interest or enforce safety and procedural guidelines. Site safety plans must be approved, as do noise and dust attenuation programs. In some cases, it’s too impractical to eliminate all noise, and alternative means are employed, such as the ‘muck houses’ used by the MTA to remove substrate for the Second Avenue Subway tunnels. Some of these strategies yield mixed results, for example, the muck houses reduced noise, but created existential problems for local businesses.

Any project involving substructure should develop a risk assessment (RA) that determines likelihoods of various delays or disruptions to the work: limited operating hours for noisy work, downtime to unblock refusals or change drill bits, redesigns to work around unforeseen encumbrances and right-of-way issues. The RA should be incorporated into the construction schedule, however, it seldom is even shared with the scheduler, who would be the only one in position to allow for contingencies in the schedule. Perhaps this is because no one wants to show contingencies in a schedule.

When it comes to substructure, all work to follow is delayed, or cannot ensue: unlike a disruption, where subsequent work continues at a reduced rate of production. This condition forces the schedule to be out-of-sequence, making necessary changes in project logic – including mitigation and recovery. It’s futile to introduce mitigation and recovery project logic to substructure work that is already known to be lagging: if excavation is late, don’t plan to mitigate during the balance of excavation, but in other scopes of work that have free-float. To do otherwise would be counterintuitive.

And as always: call before you dig!