When we think of CPM Schedule Acceleration, no one waxes nostalgic when I mention the ill-fated fast-track project deliveries of the 1990’s. That’s because they rarely, if ever, panned out. They failed mostly for lack of proper coordination between design and construction, and created perpetual concurrent delays. Ironically, the majority of latter day project deliveries seem to resemble ‘fast track,’ and fail in many of the same ways.

Lump-sum construction contracts typically stipulate that design documents are 100% at the time of signing. The fewer errors and omissions, the less the likelihood for change order work and delays. Sometimes, a contract is signed with the promise that the designer will provide the balance of the design documents in stages, within sufficient time, to comply with project schedule. The project is essentially a fast-track project in all but name. Invariably, the builder runs out of design information before it is published, and CPM Schedule Acceleration is undertaken.

Fast-track was a project delivery method intended to reduce the overall duration of a project by beginning the work before the project is fully designed. For example, a contractor could begin SOE, site clearing, excavating, and foundation, at the same time the architect is designing the structure. The contractor erects the structure while the architect designs the fitout.

‘Goodbye fast-track: we hardly knew you.

In this way, the drawings are expected in stages, with both builder and architect milestones built into the schedule. If one or the other fails to meet a milestone, there will be delays and resulting claims. The more detailed and complex the project, the longer the duration between stages. Longer term, simpler, and more predictable projects, could benefit from fast-tracking proper, and unknowingly work within that project delivery system.

Latent Fast-track

Any under-designed project will have an incomplete set of contract drawings. These are known as ‘errors and omissions,’ (E&Os), for which designers are liable, but seldom taken to task, save for egregious circumstances. Often, the designer isn’t given sufficient time to complete his work before the owner or SHs deadline, and his product goes out half-cocked. If the drawings are in fact unconstructable, the owner may later find himself in breach (of contract), and somewhat to blame.

A savvy contractor will notice the E&Os in the contract drawings, and indemnify himself against delays and costs incurred, with pre-bid RFIs, budgets, and time contingencies. As the work progresses, designers will choke down RFIs and submittal turnover to a glacial pace, giving themselves as much time as possible to make sketches in order to either complete the design, or to punt back to the contractor.

Building from ‘Sketches

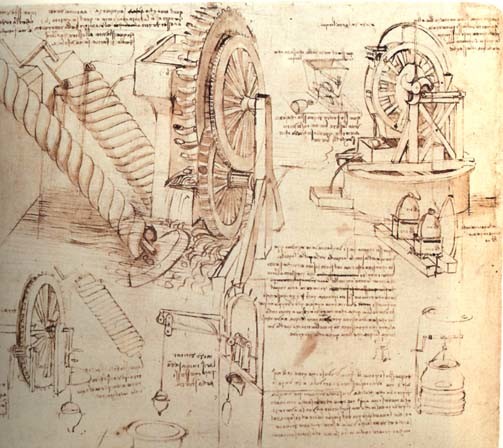

Sketches, are the lowest order of magnitude design documents that designers use to patch up loosely defined criteria. This was not always so. Brunelleschi and Michelangelo’s mechanical sketches were intricately detailed. A sketch should clarify a design, not be the design. If the design could not somehow be built without the sketch, it was an incomplete design to begin with.

As time passes, mountains of sketches drop in response to voluminous RFIs, just before they perpetuate or create a delay. This is similar to fast-tracking, only it does not benefit the owner or SHs in any way – only the designer. The more cross referencing by sketches there is, the more fragmented the design documents become, and the more likelihood for confusion and error.

‘Contractor’s are penalized a disproportionate share of delay claims by owners. These delays invariably can be traced back to design flaws, or E&Os.

More important than budgets and time contingencies are pre-bid RFIs. RFIs must continue until the design is complete. It is unacceptable for a designer to issue a ‘design intent’ sketch, and demand the details to be taken up in the ‘shop drawings.’ That’s called doing the designer’s work for him, and assuming liability.

Unexamined Acceleration

Fast-track is just as nutty as its close relative schedule acceleration, which is often based on over-idealistic presumption, and few data-driven strategies. Consider your average 3 year project. One year in design, and two in build out. However, the designer insists on 18 months instead of 12, and the contractor requires 36 months, instead of 24.

The owner irons out an agreement where the contractor agrees to begin 1 year into the design phase, fast-tracking the balance for 24 more months, for a total of 36 months. The contractor received an upcharge and net 30 payment terms, in order to accelerate 33% (from three to two years).

‘There’s even a scheduling program called ‘FastTrack’ – and wouldn’t you know it – it has 0 to do with fast-track scheduling.

As the project progresses, ‘shit happens:’ stop work order, delay in material, weather, trade issues, RFIs, and small endeavors in the field point toward systemic flaws in the production concept. Instead of working 33% faster, he is actually putting work on a pace 33% slowerthan his original 3 year duration.

‘It’s counter intuitive to expect a contractor to suddenly ‘180’ the job momentum – that’s just tomfoolery, no matter who’s selling.

Before long, ownership is demanding recovery schedules. To mollify them, the contractor must reverse his 33% production rate just to get back to 36 months, and then increase another 33% to get back on track. The later in the project recovery takes place, the less its impact and likelihood for success. That’s because construction projects aren’t like wildly fluctuating stocks and bonds, their momentum takes a lot more time to impact, and certainly more risk management than some scheduler’s bar chart.

Platforms, such as Acumen 360 Schedule Accelerator, are designed specifically to generate scenarios that are resource and data-driven, with team buy-in/push back as a facilitator to real-time decision making. Although I have used Deltek’s platforms, published and spoke on the subject, I have as yet found any interest in the building industry for the Acumen Suite.

The reasons for this is that most builders wouldn’t have a person whom they could call an operator of the software, which they themselves don’t understand, wouldn’t maintain the schedule baseline and updates, and may not have a trained scheduler in the first place. Not a lot to work with, this explains why builders seldom reap delay claims.

When a lot of VC is at risk, smart builders buckle down within their project controls department, and find a way to float a claim worth consideration. They can only do this with rigorous and accurate record keeping. This is crucial, should a claim go to mediation. Any technical errors or discontinuities within the data-set are subject to preclude the entire claim. This includes fictitious start/finish actual dated, float sequestering (hidden float), and lack of background data. Yet, even some of the largest public ventures maintain no risk assessment, and only an MS Project with which to work. What else would you expect?