benchmarking; a subtle and frequently overlooked sequence rarely represented in CPM timelines

When I post about ‘benchmarking,’ I’m usually talking about Deltek Acumen Fuse, and its Logic and Schedule modules and indices. But this post is a natural continuum of the previous posts pertaining to core and shell scheduling sequences. As I shall relate, benchmarking and surveying activities have specific deployments in the field – all of which should be tracked and forecast in the schedule.

In surveying, the term ‘benchmarking’ pertains to fixing a permanent spot-elevation on which Civil drawings will use as elevation benchmark or reference point. Ancient Egyptians and Greeks used stele. In the modern sense, ersatz stela benchmarking could be a surveyor’s nail head, pencil mark, or ground in crosshair on a stable element. Structural drawings typically reference this benchmark to align the building foundation and footprint within its lot lines, and in relation to adjoining.

Despite the power of technology, the plane geometry required for benchmarking remains elementary and immutable, and can still be done as the Ancient Egyptians did using various water level techniques, which were eventually supplanted by transit levels. Buildings still grow out of the ground horizontally, vertically, even slanted or curvilinear, in relation to established lot-lines, and at predictable trajectories. The horizontal plane, or lot, is typically identified in a given project’s Civil drawings, based off a surveyor’s metes and bounds reckoning.

The lot lines are projected perpendicularly to the ground projecting air rights. This reckoning will be confirmed both before a property sale, and as part of the contractors stake out, where he hires yet another surveyor to confirm a building’s footprint. Encroachment on a neighbor’s air-rights can result in costly litigation. In urban construction – NYC, for example, tolerances at lot lines can be very tight: a 18th century building on Charlton Street I converted maintains a lot line with its neighbor between an original, porous, two-wythe brick wall – you could stick your hand into the bedroom nextdoor.

The elevations, or ‘topos,’ are also shown in the civil drawings, typically as part of substructure, drainage and SWPPP plans. Prior to excavation, a height is taken from the surveyor’s benchmark, usually a sidewalk, or concrete or masonry. Look down at the sidewalks near any building going up and you might see surveyor marks – a nail, or little ‘X’, sometimes ground in and colored.

The Civil drawings show ‘spot elevations’- or reference points for the sub-surface work, as well,

and these are also used thereon as the elevation benchmark from which excavation, superstructure, structure and curtain wall will be referenced in the vertical plane. As the pours proceed vertically, this benchmark is continually re-verified. In addition, the extension of each slab edge must also be aligned, lest it encroach on a set-back or neighbor’s air-rights.

As concrete slab reshores are removed, a surveyor may visit to reshoot elevations not so much for accuracy, but to gauge how much the building is settling. Because mid and high-rises put substantial load on a disproportionately small area of subsurface, they are sometimes subject to compaction of the subsoil, or other support work. All of this is determined by a soil engineer, in preconstruction.

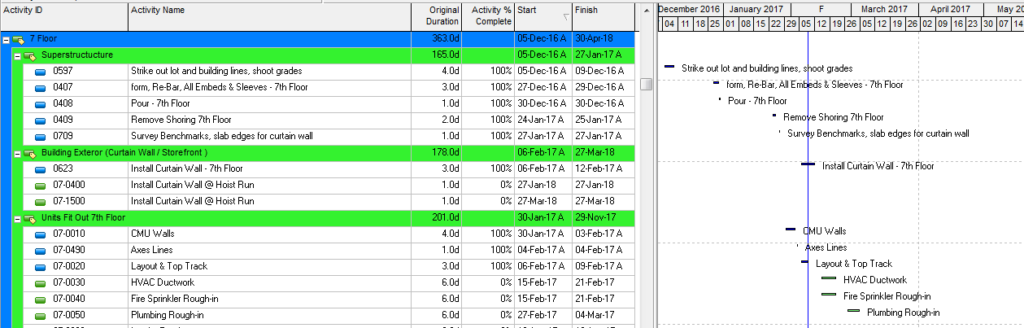

Timeline incorporating survey and layout activities. Note downtime for curing, and curtain wall hoist comeback work

Once the working platform is established above its prescribed height, layout teams can begin laying the x/y axes lines below, on top of the concrete slab. Masons can lay block, and carpenters may layout framing and glue and nail their plate, or track, to the floor. Sheet metal is run, before the interior framing follows along with the rest of the MEP trades. But then a slight hiccup: slabs rarely are poured dead-level and typically require leveling – it’s easier to return after framing with a self-leveling agent that will take up the low points for a number of practical reasons.

Naturally, consideration for the axes lines needs to be taken into account in terms of when they are struck, or restruck after self-leveling, if necessary. This sequence is where a savvy schedule will have a heads up, and have the necessary steps included in his timeline.

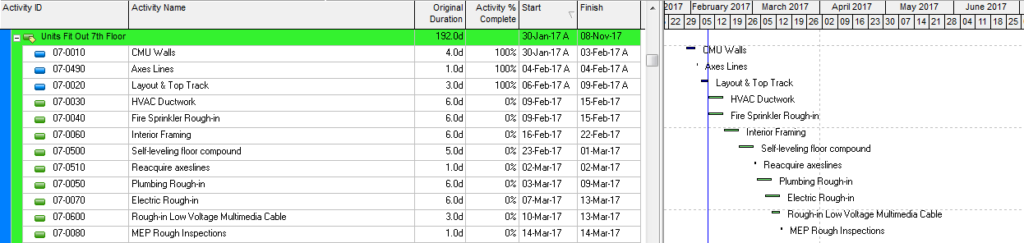

Self-leveling in the timeline. Note reacquisition of axes lines

A hotel job I was on once had 7 different color axes lines on the floor from various reworks. I asked “why?” The foreman said “some of them were superseded. The others – each trade only trusted his own lines.”

In the above example, the leveling is done post framing. The work requires that no other trades work in the same are, for obvious reasons, thus there are no concurrent activities with leveling. The good news is that self-leveling sets up super-fast, and can be worked on the next day.

Survey/resurvey, benchmarking, axes lines, and layout, are all standard procedures yet seldom adequately represented in most contractor’s timelines. Everytime a new partition, pipe, or duct is installed, its position can be traced back to layout lines and x/y/z reference points that have their basis in the drawings. Giving short shrift to these activities in the schedule is done so at one’s on peril.