Construction negative productivity rates plague the building industry, as other industries enjoy modest growth. Industry leaders and academics struggle to come to terms with this reality, even as it continues to get worse. However, the focus causal factors tends to be simplistic, and predictable. Yet, new research will show – what I have always suspected – that the biggest drain on productivity is low morale.

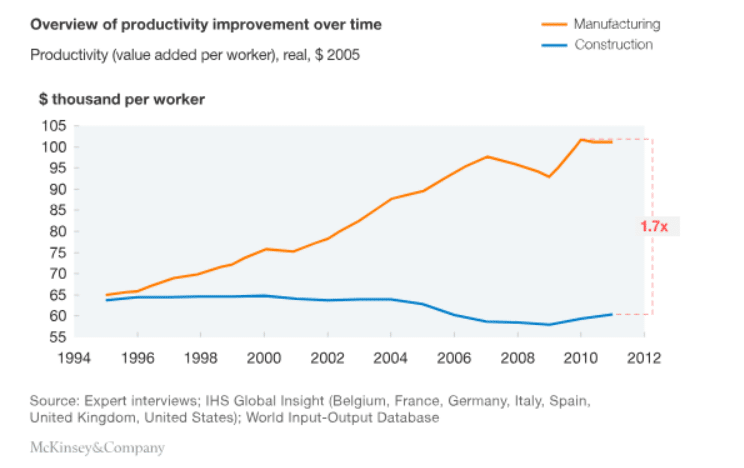

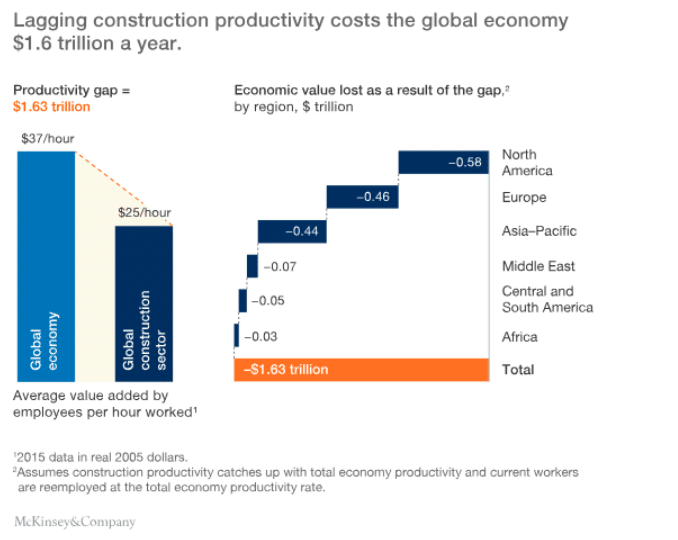

Construction negative productivity is a confounding and costly global conundrum given that peer industries show modest to aggressive growth (see graph, below). Despite technological advances, such as web-cams, IoT, semi-automated robotic operators, drones, the industry fared poorly through 2013, although on a barely noticeable upward tick.

However, the study was taken in 2013, when a lot of that technology was nascent, even outside the building industry. But if we look at 2015 rates, we see a continuing trend:

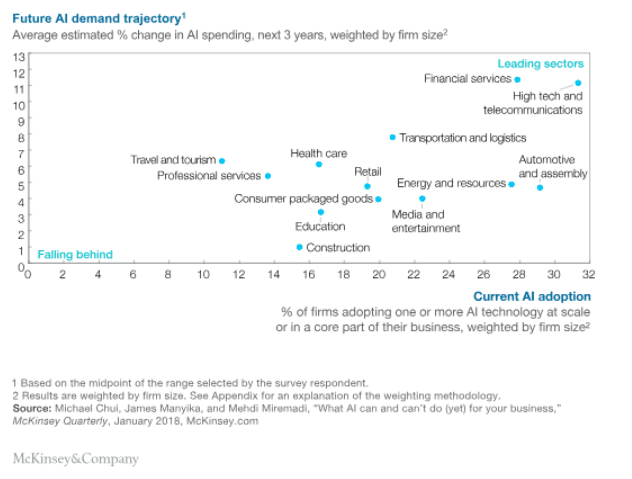

McKinsey is betting on AI making an impact on the design industry, but clearly less so in the building industry, according to the chart below.

McKinsey, using a 2013 study, attributed blame across a variety of factors for negative productivity. It is one of the few available qualified resources on the subject. My comments to McKinsey bullets appear below each:

- Poor organization. Decision-making and procurement processes do not have the speed and scale required.

Decision making is more the bailiwick of the owner and design team, such as sitting on RFIs, and delayed design documents. It also includes downtime for negotiating change orders, or payment apps. Poor procurement habits are back-office problems that hang up the site management team and their personnel. Without efficient vendors and specialty contractors by-out practice, projects will founder into negative productivity.

What McKinsey does not highlight here is conflict in the chain of command. Management teams in the building industry are always shuffling leadership within and between companies, as they get burned out on a project, and have to move. As they leave, people replace them, breaking continuity. This trend does not avail morale, as I shall demonstrate.

Many contractors and construction managers make the mistake of replacing personnel with new hires, instead of from in-house or promoting existing staff. That’s counterintuitive because companies lose money in new hire training costs that average 21% of their salary, and further poison morale with disappointed personnel hoping for promotion.

Bringing in project executives and other business managers with no formal management training shows in the way they interact with the project team. Many such managers become saber rattlers merely making noise to mask their lack of acumen.

- Inadequate communication. Inconsistencies in reporting mean that subcontractors, contractors, and owners do not have a common understanding of how the project is faring at any given time.

Inadequate communication plagues especially specialty contractors who don’t always have the infrastructure and personnel as general contractors do. When they do communicate, it can be woefully inadequate. I also include here sequestration of information by the design team, as well as poor management of communication with the design team, such as when submittal reviews generate more questions than they do answers, forcing repeat cycles.

- Flawed performance management.

I thought this had more to do with the actual building of the job, including safety management, quality control, and accessibility. See my post ‘The Why of Suck.’ On the other hand, site managers are frequently given under-skilled resources to achieve KPIs that are outside of their skill set or far lower than the work dictates: to paraphrase, always the lowest qualified bidder. It’s implausible to expect unskilled personnel to achieve quality results, regardless of who’s the PM.

- Contractual misunderstandings. The procurement team typically negotiates the contract, and this is almost always dense and complicated. When a problem comes up, project managers may not understand how to proceed.

This means, for example, that your concrete team demobilizes before all concrete is poured because the drawings failed to include a large beam too big to pour by hand. The contractor negotiates the omitted work with the owner and trade, a change order is processed, and the work is finally executed, albeit at a higher cost, but worse – delaying the critical path.

I’ve seen trades show up on site with ‘manicured SOWs.’ A manicure denotes a manipulation. For example, a trade might offer tribute in return for a ‘tweaked’ SOW, say steel instead of brass pipe, or 5,000 PSI in lieu of 9,000 PSI concrete. That’s the opposite of a misunderstanding, that’s bait and switch. Many of these deals are cut by former procurement agents, wherein the contractor is left holding the bag.

- Missed connections. There are different levels of planning, from high-end preparation to day-by-day programs. If the daily work is not finished, schedulers need to know—but often don’t—so that they can update priorities in real time.

There is a general misunderstanding about the CPM and the way schedules are baselined and maintained by anyone other than the scheduler, and often the scheduler himself. The shortage of trained schedulers with field experience affects the quality and level of exactitude their work product, which is why out of sequence schedules are commonly abandoned altogether.

- Poor short-term planning. Companies are generally good at understanding what needs to happen in the next two to three months, but not nearly so much at grasping the next week or two. The result is that necessary equipment may not be in place.

I think the opposite is true. I always correct lay-people that forward passes in my schedules are always finalized with the two-week look-ahead. If a contractor can’t see what’s right in front of him, how can he see what lies ahead? -he can only fantasize about it. I believe that long-term planning is a bigger problem – not procuring long-lead items is a classic.

But that’s no excuse not to allocate enough qualified site managers and leadership people when they are needed. Of course, personnel pitch in to fill voids of absent job positions, and many companies might try to get by with less doing more. But making that the rule rather than the exception never works out in their favor. You can’t expect personnel to absorb 50% more workload each week at the same output rate.

- Insufficient risk management. Long-term risks get considerable consideration; the kinds that crop up on the job not nearly as much.

The building industry seldom uses risk management in any project under $1B. More colloquially, failure to plan ahead with adequate finance and resources is a best practice of risk averse managers

- Limited talent management. Companies defer to familiar people and teams rather than asking where they can find the best people for each job

As I alluded to above, no factor is weighted for low morale in McKinsey, I would assume for lack of sound research at that time.

Constantly outsourcing leadership positions demoralizes those working under that position who had been dreaming of a promotion. What’s more, finding available “leadership talent” in today’s market is slim-pickings, given the vast shortage of quality managers candidates. That means, a lot of idiots are put in leadership positions, which further humiliates the team.

Contractors themselves are to blame for construction negative productivity. Underpaying, denying raises and promotions, they never really cultivate any talent in their people, giving them know hope of growth. A company that fails to show appreciation and recognition for its personnel can’t expect those same folks to be motivated. When people realize that their company doesn’t really care or appreciate them, they begin to become unhappy in their work. As their morale and esteem dwindle, loathing is stirred, and productivity thwarted by unwillingness to put out anything more than the minimum.

When workers are unhappy, they slack-off, or ‘take a piss,’ eventually leaving, creating construction negative productivity vacuums. As each worker slows up, so does their crew’s output. The ones who don’t leave will work in their demoralized state at a far less productive rate than had they been happy. They will take longer and more frequent breaks, and waste time faffing about. Overtime and shift work are off the table.

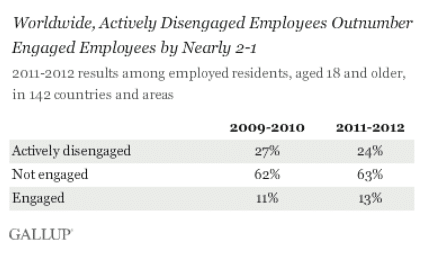

Only 13% of employees worldwide are engaged at work, according to Gallup’s new 142-country study on the State of the Global Workplace. In other words, about one in eight workers — roughly 180 million employees in the countries studied — are psychologically committed to their jobs and likely to be making positive contributions to their organizations.

Alternatively, happy personnel – i.e., people – will be far more productive, some exponentially. They take home work, work through breaks because they’re rapt in their zone, make fewer mistakes, and complain far less. Even between crews, low morale productivity curves can be demonstrated.

If a happy in their work mason crew of 6 can do the work of an unhappy crew of 8. That’s a 25% production rate factor: an inspired team of slower workers can outpace a crew of frustrated faster workers.

My point is that demoralization and unhappiness in the workplace belongs at a much higher factor rate on the McKinsey scale in any industry. Because it’s hard to measure, we don’t read a lot of studies on the subject. Not until 2015, did the University of Warwick publish a study that on average, ‘happiness made workers 12% more productive.’ A professor leading the study went on to say

“Companies like Google have invested more in employee support and employee satisfaction has risen as a result. For Google, it rose by 37%, they know what they are talking about. Under scientifically controlled conditions, making workers happier really pays off.”

And on bottom-line –

“We find that human happiness has large and positive causal effects on productivity.

Construction negative productivity driven by poor morale is nothing new, and not limited to any one industry. Low productivity driven by poor morale is also associated with degraded levels of quality control. Happy workers make fewer mistakes, and produce far better quality product. An unhappy worker has no incentive to produce anything above the minimum expectation.

As an oversight reviewer and quality control expert, I can always tell when someone cut corners, or hid mistakes instead of correcting them. If someone is happy in their work, it shows in the quality of their product (assuming they know what they’re doing). Sometimes it’s easy to mistake naivete for ignorance or carelessness, when it’s merely a case of untrained, or otherwise inept personnel.

You’d think that something so obviously broken could be easily fixed, but then you’d have to assume their was an incentive to do so in the first place. You’d also need a relatively sophisticated HR program that developed morale reinforcement initiatives with real rewards and benefits.

This way of thinking can be thought of in a single word devoid of most contractor or construction manager’s lexicon: cultivate (people). Google saw it work for them. But the building industry is a bit more squirrelish – and a whole lot less sophisticated than Google: the industry is not known for its ‘people skills.’ I suppose we’ll just have to wait another lifetime for the building industry to get the memo.