In requests for pricing (RFPs) or invitations for bids (ITBs) there are a number of requests or requirements that typically fall under the radar. One such is a seldom observed request generally known as bid schedules. Not to be confused with preliminary schedules – which are typically required within thirty-days of contract execution – bid schedules – as the name implies – are intended to impart a high-level outline of how a contractor envisions the trajectory and timeline of a given project.

Since preliminary and final schedules are the exception from contractors who underperform in that capacity, bid schedules are even more elusive, as it seems to be a discretionary expense contractors either fear or disdain. Just like laborious bid breakout requests, they are unwilling to go the extra yard if a project is of low interest. This practice undermines the ability of contractors to better position themselves for bid awards, and may even cause their bid to be rejected as non-compliant with an RFP/ITB.

The private sector is more tolerant of incomplete bid submissions, willing to overlook them, whereas public work conversely is more likely to reject a bid out of hand. Some developers are beginning to become more savvy in their understanding and appreciation of project schedules. This knowledge is gained from real-time experience of projects that did not make deadline – costing them considerable overages. Instead, they rely on no damage for delay clauses, or impose liquidated damage clauses. Either scenario is a losing proposition to the contractor whether there is a project schedule or not.

Contractors who regularly utilize bid schedules often realize an advantage over those who don’t. The absence of a bid schedule can portend to low expectations of time management and schedule development that will steer many developers and stakeholders away from a contractor. Those contractors utilizing bid schedules make strong statements and arguments about how they practice (or eschew) project controls.

It’s confusing to consider the possible reasoning for contractors to give any schedule the same level of importance as their cost estimates, as they should be intrinsically related, yet low-priority for scheduling is commonplace. This is a disservice to developers and stakeholders, but it also severely handicaps contractors’ ability to make viable and coherent extension of time claims (EOTs) or to litigate when necessary. For this reason, only a tiny subset of delay litigation ever finds in favor of the contractor.

Whether required with a proposal or not, bid schedules make sense because they present the contractor as the exception to other bidders who routinely ignore the requirement. If the contractor is the only bidder – or one of the few with a bid schedule – there’s a strong likelihood that he will present his bid in a more favorable light than the competition.

The beauty of bid schedules are that they can be done in a short time frame, and for a reasonably affordable fee. Simple as bid schedules may be, a contractor may elect a project manager to generate bid schedules. Typically, such a submittal is one-off: a project manager untrained in CPM will be hard-pressed to generate even the most basic timeline. For that reason, all CPM schedules should be developed and maintained by professionals trained in the CPM.

Exactly how and what bid schedules should represent is a matter of debate, as there are any number of formats to choose. It helps to keep things concise without omitting critical information. I like to format my bid schedules in a way that they can be directly developed into the next phase – preliminary baseline.

My bid schedules for a ground-up high-rise include at minimum the following WBS as level of effort (LOE) activities:

- Preconstruction

- Production

- Close out

In addition, the following milestones:

- NTP

- Mobilization

- Weathertight

- Substantial Completion

- TCO

Once the primary WBS is established, I further develop sub-WBS categories as follows:

- Preconstruction

- Permitting

- Design deliverables

- Procurement

- Submittals and Approvals

- Mock-ups

- Production

- Demolition or excavation

- Substructure

- Superstructure

- Curtain Wall

- Interior fit-out

- Punch-list

- Close out

- Testing & Commissioning

- Agency sign-offs

This basic structure lends itself well to most any traditional high rise sequences. The trick is to determine correct duration and sequencing that can be expounded into a preliminary baseline. Ideally, a general contractor will either request input from his specialty trades (good luck with that) or develop his own project sequencing and then (hopefully) request feedback from trades.

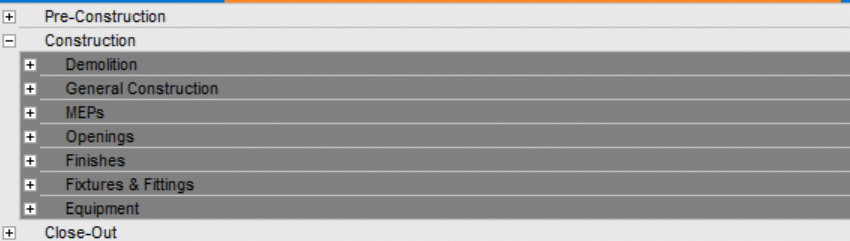

Sometimes you want to go the extra yard – especially if a bid schedule is mandatory. The example below is of my standard WBS for bid schedules for one of my retail clients:

If a contractor specializes in just one or two types of construction, it will be easy to template his bid schedules, such that he need not reinvent them for each project. Indeed, I maintain templates for clients who specialize in one discipline of construction, which maintains a low unit-price for future bid schedules using the base template. I don’t think there is a better investment, or one with such an obvious cost-benefit to a contractor, than the humble bid schedule.