Administrative Requirements – 01 31 02 Construction Progress Documentation

In 01 31 01 Project Management and Coordination, Part I, I discussed how planning, coordination, meetings, and documentation administrative requirements can increase and become extreme construction project cost risks that are difficult to detect and rectify – mostly for lack of clarity in quantifying and tracking resources. These administrative requirements are frequently conflated or bundled with other general requirements, general conditions, and project overhead that also tend to lack clarity, creating confusion that is resistant to analysis and remediation.

A second sub-heading of Administrative Requirements – 01 31 02 Construction Progress Documentation – presents specific challenges iterated below, the most daunting of which are those concerned with project scheduling and construction progress reporting, which are related administrative requirements.

This post will demonstrate the mechanics of how basic administrative requirements for project documentation can quickly become budget vulnerabilities, and increase project risk profiles in a myriad of ways that defy quantification, and go beyond the basics of project delivery strategy.

01 31 02 Construction Progress Documentation (abbreviated)

01 32 13 Scheduling of Work

01 32 16 Construction Progress Schedule

01 32 16.13 Network Analysis Schedules

01 32 19 Submittals Schedule

01 32 23 Survey and Layout Data

Like Project Management and Coordination, Construction Progress Documentation includes administrative requirements that frequently understate anticipated levels of detail and expectations, such as multiple reissues, and extended data gathering and modeling. Only deep experience with complex projects allows us to read between the lines and visualize the potential for these basic services to expand into endless permutations of document preparation and management that erode project budgets well before a project has a chance to develop.

The burden of resource and program expansion lies with the contractor who must provide the services, however, it is often incomplete or erroneous project design documentation generated by the design team that creates the condition of a contractor ‘spinning his wheels.’ Despite design errors and omissions (E&O), contractors contribute to the problem by failing to deliver sufficient documentation according to administrative requirements. When supplemental efforts become necessary, they are hard put to produce if they’ve been unsuccessful at furnishing basic administrative requirements.

01 32 13 Scheduling of Work

CPM scheduling should be the lifeline and pulse of any complex construction management effort, as it directly drives time and budget. Despite that relevance, surprising few contractors create a project baseline schedule sufficient to purpose, nor do they maintain the baseline along with updates.

Although the CPM schedule is an asset to contractors – a management tool that forecasts time and resources, they tend to begrudgingly provide the service only when pressured by ownership, who demand the information. Contractors thus resent the expense for the effort, and invariably underperform.

A baseline schedule specification will iterate boilerplate administrative requirements. requirements, as well as specific ones – such as black out periods, contract milestones, and provisions for owner force work (OFW). Sometimes the WBS structure itself is dictated, as is frequent with public and government work.

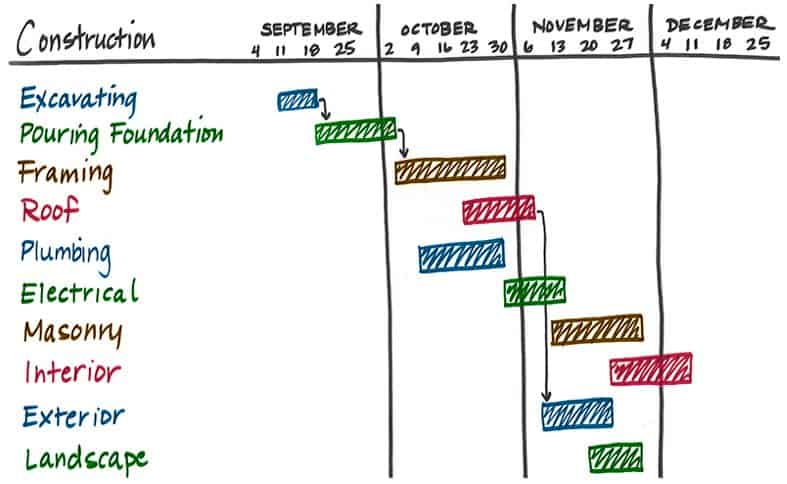

The baseline schedule is an extension of the preliminary schedule, which is typically issued within 30-60 days of project award. Preliminary schedules are broadstroke networks that show the big picture in condensed WBS, or what is known as Level One (high or executive level) or Level Two detail. The Schedule Level of Details is defined by the AACE.

Once a high level preliminary schedule is issued, it is reviewed for contract compliance – or the correct representation of major phases and project milestones. This schedule is then developed to show higher levels of detail – to Level 5 – which is comprehensive enough to lock-in as the baseline schedule: that to which all progress schedules are compared for performance review.

Subsequent to the baseline schedule, progress schedules (see below) will represent work-in-place, and real-time projections of remaining work. As a project progresses, it is subject to be affected by several factors that require resequencing, recovery, and mitigation, all of which are iterated in the specifications, albeit without expected scope of work, as that is an unknown. It is within these extraneous schedule efforts that enhance resources are required to execute – resources that a contractor seldom is compensated for. The level of enhancement can impact budgets in dramatic ways.

A reality check of an average schedule effort will bear surprising facts: for example, a contractor has a two-year project. He allots 160 man/hrs to achieve the baseline, and 16 man/hrs for each update or 384 man/hrs (16*24) , for a total of 544 man/hrs. Assuming he expends these 544 man/hrs, if there are large scale and constant resequencing and change orders undertaken, and complex recovery and mitigation efforts, his scheduling budget could easily double.

If the contract requires a full-time scheduler, the excess hours may be billable and absorbed within budget. However, if the project is delayed, these extra efforts may not be remunerated – just like extra general requirements and general conditions. Rather, contractors often prefer to outsource the workload to scheduling consultants – which they perceive as only part-time – hoping to control their budget. Unfortunately, the dearth of talent in the CPM scheduling industry renders that strategy implausible.

For that reason, large projects should budget for a full time scheduler, regardless that his salary may increase soft-costs, or profit-margin. As a measure of due diligence and accountability, it is the right thing to do, yet it is also a rare thing: scheduling is too often perceived as a fifth-wheel – an unnecessary requirement that contractors resent. That strikes us as an unwise and self-defeating industry perception that contributes to budget failure.

01 32 16 Construction Progress Schedule

Construction Progress Schedules, or schedule updates, mark the come and go of every project. They are typically issued monthly, and accompanied by narratives that include administrative requirements. outlined in this section. As conditions change, updates will require resequencing that involve the scheduler’s team mates – superintendents, project managers, and trades and vendors. Meetings for resequencing efforts will exacerbate the change already affecting the budget adversely.

Contrary to popular belief, the scheduler should not be the person responsible for calculating the percentage of work in place, but project management and bookkeeping. That’s because progress may be difficult to assess. On the one hand, there are the trades’ monthly applications for payment, which must be reconciled with the general contractor’s assessments. These values are often ‘guesstimated’ by either duration, physical percentage, or units, in the various accounting, complicating progress scheduling and forecasting. If parties don’t use the same method of reporting progress, the master schedule update will become problematic.

“Oversight consultants make their money trolling for technical flaws in the CPM schedule, rather than evaluating real-time logistics of which they have only a general comprehension

Progress updates can easily be managed using collaborative or shared files, for example, Primavera 19 generates spreadsheets of activities that can be filtered for easy input and review. Only a few columns need to be input: actual start, percentage complete, and actual finish. The spreadsheet can then be uploaded back into the master schedule update.

Despite the simplicity of this system, project management and trades will prove quite resistant to updating the progress worksheet. Only if the general contractor creates an imperative will the data be gathered and input in a timely manner – if at all.

As a project is delayed, notice of delay (NOD) letters are typically required to document a prospective delay, followed by an extension of time (EOT) request, which are routinely rejected out of hand. Even so, EOTs can be tedious and time consuming efforts that are seldom compensable. Part of the reason for that is because contractors are typically feckless in their CPM schedule management – not having the wherewithal to provide support documentation in and with the CPM schedule.

Also contrary to popular belief, the generation of a resequenced schedule requires executive project management contributions that are routinely ignored, and reduced to oversimplified high level roles. Indeed, high-level schedule management can not be maintained without and understanding of the parts that make up the whole. Executive level managers are afraid to be exposed for having jumped the shark of CPM training, or feign they have acquired this knowledge through osmosis. Few prove willing pupils to be educated in the art, and rather, would arrogantly act as though they master the knowledge, despite knowing a few spare details.

Insofar as CPM schedule approvals, an owner soon finds himself over his head, and will seek an outside consultant. The ratio of unqualified to qualified professional CPM oversight consultants is extremely high: most of them know but little of the craft and use inexact methods for calculation, while at the same time ignoring industry standard, and professional level forensic analysis platforms – such as Deltek’s Acumen Fuse. Indeed, most oversight consultants I have worked with have never even heard of Deltek.

Oversight consultants make their money trolling for technical flaws in the CPM schedule, rather than evaluating real-time logistics of which they have only a general comprehension. For that reason, it’s not unusual for an update with an EOT is continually rejected before it is accepted – if ever. At the core of their mission, is a battle for negative float ownership that ignores the core responsibilities of oversight,and burdens contractors with supplemental conditions.

RA: high to very high

01 32 16.13 Network Analysis Schedules

Network Analysis Schedules are a function of the CPM project schedule. They are a graphical representation or network diagram – such as a Program evaluation and review technique PERT chart. These can be helpful for executive level coordination, or to simplify GANTT charts that are too complex to visualize. Some specifications make mention of these diagrams, yet the requirement is seldom clear or enforced. Many project management operators are wholly unaware of such a system, for lack of CPM training.

RA: low

01 32 19 Submittals Schedule

The submittal schedule must be developed in reverse, from the time program is needed on site, backward through delivery, fabrication, approval, reviews, submittal(s), and procurement. Typically, long-lead and major trades are planned. These sequences must be input into the baseline schedule, and there tracked.

The durations for submittal and review windows should be noted in the contract documents, and the submittal schedule should reflect those durations. Savvy contractors will anticipate additional submittal and review cycles, and make allowance for them in the respective activities.

Baseline schedules are frequently conflated with shop drawing logs, which they should never be. The latter is a far more comprehensive document, and typically has considerably more line items than the preconstruction WBS of the baseline. Any critical path driving submittal review should always be tracked in the schedule in the expectation that it will drive a delay path to be represented in a potential EOT.

The submittal schedule tells the project team what to expect and when, such that they can plan and assign their resources. It is not the same as 01 33 23 Shop Drawings, Product Data, and Samples, the actual process – discussed in 01 33 00 Submittal Procedures.

01 32 23 Survey and Layout Data

The surveying component of Survey and Layout Data can be a misleading requirement in that it is frequently misinterpreted and reduced to a one time service, for example, a LIDAR scan of existing conditions, and identification of benchmarks. It should include continual survey services of new work in place, and its relation to existing adjoining program. Layout data would appear to be part and parcel, a product of continual surveying.

The failure to continually survey work in place creates risk that can’t be overemphasized. It’s not enough to layout from surveyor benchmarks and hope the work conforms to it, but a contractor must continually survey work in place. For example, there have been contractors who failed to survey a building’s elevations and plumbness as it goes up, only to find out that concrete decks are low, out of level, or that the building is not rising at ninety degrees, when it’s too late to address

RA: high