Fragmentation of resources on a construction site is a commonplace phenomenon that deprecates even the most diligent CPM scheduling efforts. Fragmentation happens when typical sequences – such as floor-to-floor/area-to-area – become disrupted, and the baseline schedule sequence becomes broken, leaving an abundance of out-of-sequence errors that require revised project logic.

Ideally, a vertical project fit-out will proceed one floor to the next following the superstructure and when the structure is weathertight. The same is true of horizontal programs. In this way are a contractor’s resources allocated and assigned in what he believes is the most efficient manner to prosecute the work. Yet, as a project progresses, various encumbrances may disrupt the predictable flow of available work areas. These include program conflicts, RFIs, redesigns, weather and labor dispute impacts, and procurement/supply chain issues that drive the baseline logic astray.

Thus, in lieu of moving trades from one floor to the next, trades become dispersed into dissociated areas throughout the worksite. This scenario creates challenges for project managers to monitor the trajectory of the project. Areas are mobilized, half-completed, and suddenly abandoned due to the latest encumbrance, in such a way that no area can be completed or prosecuted in a linear fashion: trades must constantly mobilize, demobilize, and remobilize elsewhere, causing coordination and continuity havoc that will ultimately be the project build-out undoing.

Instead of following the schedule, trades work where they are able, or not encumbered, based on day-to-day needs determined by project managers – i.e., they no longer follow the baseline schedule, if ever they did. As they disperse throughout the building site, general conditions for oversight, labor, and coordination, begin to soar, causing trades to spend more resources and lose productivity.

A scheduler must bob and weave to fold in resequencing as it happens before his schedule becomes obsolete and beyond repair. The longer he waits to correct out-of-sequence logic, the greater the likelihood for utter dissolution. It’s not uncommon for the schedule to be abandoned by the field team, only to become merely a document to meet contractual obligations, or mollify stakeholders. In such cases, the schedule no longer can represent coherent forward-pass forecasts, but merely document as-built progress: the work now drives the schedule, not vice-versa.

As fragmentation of resources increases baseline logic becomes increasingly invalid. Many schedulers prefer to remove out-of-sequence relationships, and replace them with non-driving logic – merely in order to resolve DCMA14 logic-errors. Yet, on out-of-sequence projects, it is common for activities to begin before their baseline driving predecessor, and without driving logic. In such cases, I delete the out-of-sequence logic – even if it means an activity no longer has a predecessor. This practice will befuddle the layperson (any person untrained in CPM scheduling) who is beholden to the royal DCMA14, but it makes for more concise schedule management: if an activity started without a driving predecessor, it doesn’t matter if you delete non-driving predecessors – that logic is a moot point. For those who prefer otherwise, an ersatz activity can be assigned to all activities lacking a predecessor.

There are several preventive measures a scheduler can take in expectation of potential fragmentation that will minimize resequencing measures, and even rescue a schedule for which demise is imminent. These are a measure of how well the baseline is planned. If the baseline is not solid, resequencing alone cannot rescue it:

Avoid redundant logic: redundant logic makes resequencing an unnecessarily tedious undertaking. There are two ways to manage redundant logic that I know of. The simplest can be exemplified in the laws of association: if ‘A’ is tied to ‘B’, and ‘B’ to ‘C,’ then ‘A’ need not have a direct tie to ‘C.’ ‘A’ to ‘C’ is redundant. Thus, when calculating project-logic, the laws of association are the golden rule. Such redundancies also elevate the phenomenon of merging logic that creates unnecessary pinch-points when evaluating metrics. Merging Hotspots (a Deltek term) will adversely impact risk profiles by forcing unnecessarily high risk assessments.

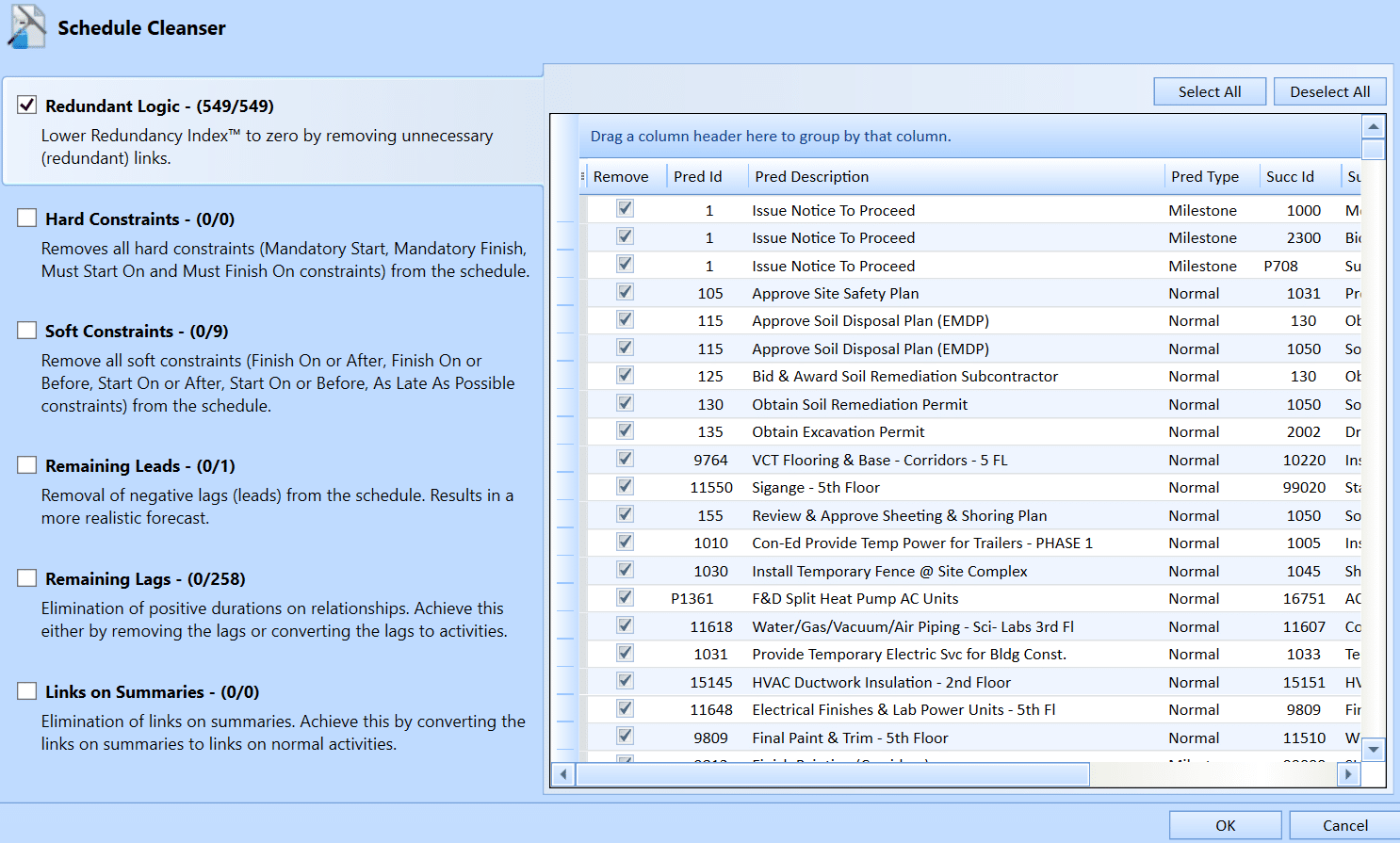

The second measure is using the Cleanser® feature, in Deltek’s Acumen Fuse platform. The beauty of that tool I can impart in a recent schedule review: a scan of a Primavera xer file with some two-thousand activities, including some 4,250 relationships. Best practices dictate that an average of 1.5 relationships/activity is optimal, thus the logic volume was suspected to include redundancies. Seconds later, Fuse generates a list of 750 redundant relationships. Finally, the best news is that these redundancies can be deleted with a keystroke, without affecting project logic. Without Acumen Fuse, these relationships must be deleted manually.

Ideally, redundancies are avoided in the baseline. As a final measure before the baseline final draft, I run Cleanser in order to detect redundancies, and any other logic deficiencies. I pride or challenge myself on keeping these to a minimum This due diligence makes for a sounder work product beginning with the baseline, and provides fluidity and the ability to more easily rebaseline or resequence as the case may be.

Finally, the chaos and productivity losses created by out-of-sequence and fragmentation can be difficult to quantify. If productivity loss can’t be adequately quantified and represented in a CPM schedule, the likelihood of remuneration to the trades for disruption or EOT claims by ownership is infinitesimally small, as is the case within the judicial system. Appreciation of that fact should inspire more trades to maintain their own CPM schedules, and track productivity losses within that document as they happen.